Landscape Works

In Search of Sharawadgi with Piet Oudolf & LOLA.

Contributions by Joseph Beuys, Kie Ellens, Anne Geene, Giuseppe Licari, Geert Mul, Darcy Neven, Vijai Patchineelam & Adrijana Gvozdenovic, Sanne Vaassen.

Exhibtion Design Sam Jacob Studio, Graphic Design Fraser Muggeridge studio

05-06-2021 to 17-10-2021

In Search of Sharawadgi presents the ideas and dreams of Piet Oudolf and LOLA Landscape Architects. Piet Oudolf is Holland’s most wellknown garden designer and he has completed such famous projects as the High Line in New York.

The exhibition takes visitors on a journey, showing them how public gardens and landscapes across the world have been transformed. From the High Line in New York, the gardens of Hauser & Wirth in Somerset, the Star Maze in Tytsjerk to the Leisure Lane in Parkstad. Familiarise yourself with Oudolf’s and LOLA’s ultimate vision for the future: a global forest against the warming of the earth. It is a dream that can start in anyone’s garden, however big or small.

On our journey we are accompanied by the artists Joseph Beuys, Kie Ellens, Anne Geene, Giuseppe Licari, Geert Mul, Darcy Neven, Vijai Patchineelam & Adrijana Gvozdenovic, Sanne Vaassen.

With new and existing work, they present us with an extraordinary perspective on both the discipline of garden design, and major issues such as global warming and the impact of nature on our well-being.

It’s a strange thing to make an exhibition about landscape in a basement. Not on the land but in it. Basements are where you’d usually find the most interior of worlds – jazz clubs, speakeasies, places that take you out of the realities of the surface of the planet into experiential fantasies. Not only spaces within a building, but psychological interior landscapes too.

But maybe because of that, a basement is the best place to think about the meanings and significances of landscape. Of all the products of human culture, landscape is the hardest to recognise as a product of human culture. Perhaps that’s because, unlike other forms of creative practice, its medium is the world. The trace of the designer’s hand and the multitude of decisions involved in creating landscape evaporates. The plants, fields, roads, forests and parks that are precipitated no longer register as the result of choices and decisions but seem instead to appear inevitable and eternal truths.

Yet even wilderness (such as it remains) is designed. Maintained, managed, and framed by policy and legislation.

Perhaps that’s why landscape is best considered when one is separated from it. In the dark interior where architecture submerges itself into the ground, maybe that’s where the ideas and examples of how the world is made can be revealed.

The approach to the design of the exhibition was to merge sensations of landscape with sensations of interior, mixing scenography with logic, merging scales and dimensions. To take the visitor on a journey – a promenade as another age of landscape designer might have said.

We begin in a forest, where tree trunks suggest somewhere else, yet also resonate with the distinctive Glaspaleis columns. Emerging from this artificial forest into a space enclosed by a wallpaper forest. From 3d to 2d, from 1:1 to the scale of a region. Beneath your feet a plan, at another scale, rendered as a carpet as if you are stepping into the spaces of a Piet Oudolf drawing. A drawing intended to instruct the setting out of a garden becomes a landscape in its own right.

Both elements are exhibits but also recall the long traditions of vegetation as interior design motifs. From the carved stone capitals of ancient columns, wallpapers full of foliage, rugs whose patterns swirl with flowers. Are we in a room? A landscape? An exhibition? A place? Hopefully all, simultaneously.

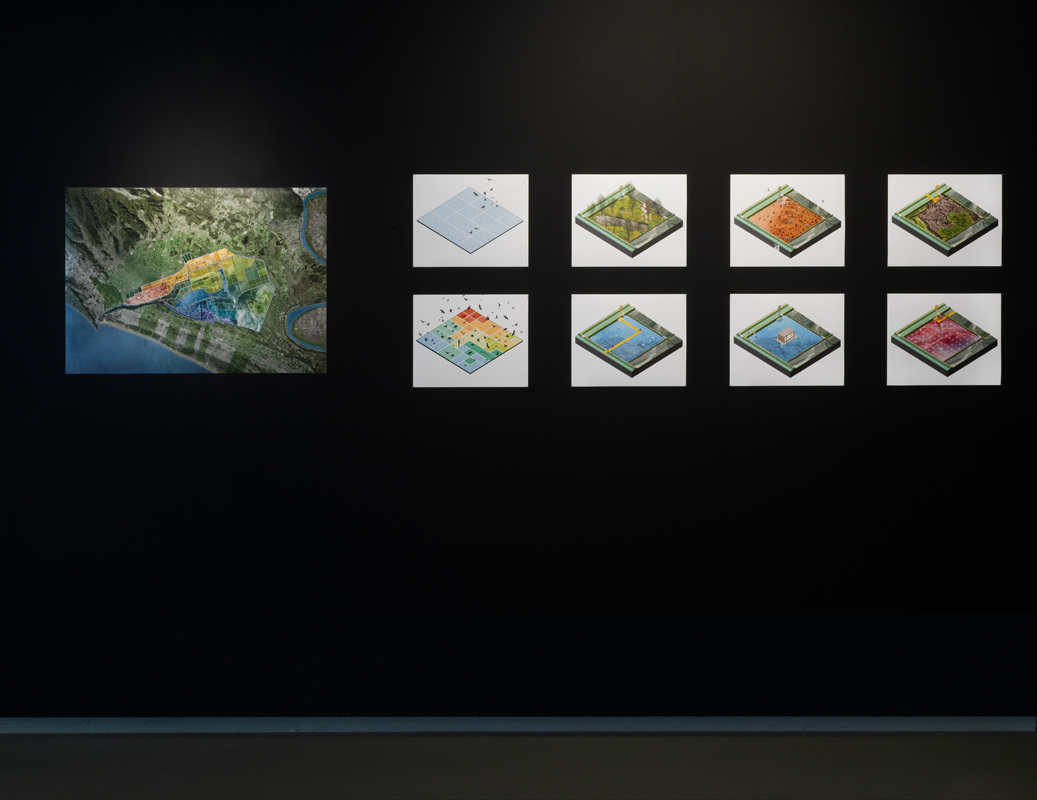

We find ourselves exploring the High Line represented as a linear hang over and an abstracted Manhattan grid. Or encountering fragments of the designers studios and offices (the subjects as objects). Or walking through archival shelving that takes on qualities of topiary hedge. We find a greenhouse, reminding us of our own domestic relationships to landscape through gardening. But beyond a view of post industrial landscapes and the challenges of global environmental crisis. The contrast in scale draws a link between our own gardens and global environmental catastrophe.

There are tricks like a 3D lenticular print that responds to the viewers movement giving depth and animation to otherwise flat photography. There are objects at 1:1, design drawings and documentation. The mix is a tactic that addresses the perennial problem of an architecture exhibition: How do you show something that is somewhere else?

Varying media and modes of display, asking visitors to engage in different ways (with their body, their imagination, their intellect) makes the experience itself a kind of voyage shifting in scale and mood. Can an exhibition itself become a landscape? (or, conversely, is a landscape a form of exhibition?)

This is an exhibition about the work of Piet Oudolf and LOLA – both explicitly landscape designers. It’s important to show their work and the places they create and to give space to their approaches and attitudes. But we know too that landscape is never a singular thing. Bringing work by others – artists, filmmakers, workers – alongside the headline acts brings voices (and tones) recounting their own experiences and ideas of landscape. Blurring boundaries between design and art, between creation and comment, suggests the complexity and polyphonic reality of landscape. Landscape as a site where auteured visions combine with the messy world beyond: A complex intertwining of the individual and the collective, of the poetic and political.

Back to the basement gallery with its constructed interior landscapes, imaginary places, changing views, scales with mixed media and multiple voices. These aren’t simulations. Or rather, they attempt to say that all landscape is – despite its appearance – an unnatural act. And that our pressing challenge is to create, manage and use our landscapes in ways that acknowledge our environment as a synthetic creation where ecological dreams are played out in the real world. The question the exhibition poses is what kinds of dreams could landscape be?