Blind Spot

An editioned print available from Betts Project

Architectural drawing is a strange and powerful tool. It is simultaneously a means of depiction and a way of constructing the world.

That’s why, beyond the conventions of practice, the politics of the architectural image remain so significant. The drawing is the world we construct: its own ideas of subject, its modes of representation and so on are hardwired into the worlds they depict and also become armatures of the world to come. Just as language constrains what it is possible to say, so too does the definition and nature of architectural drawings.

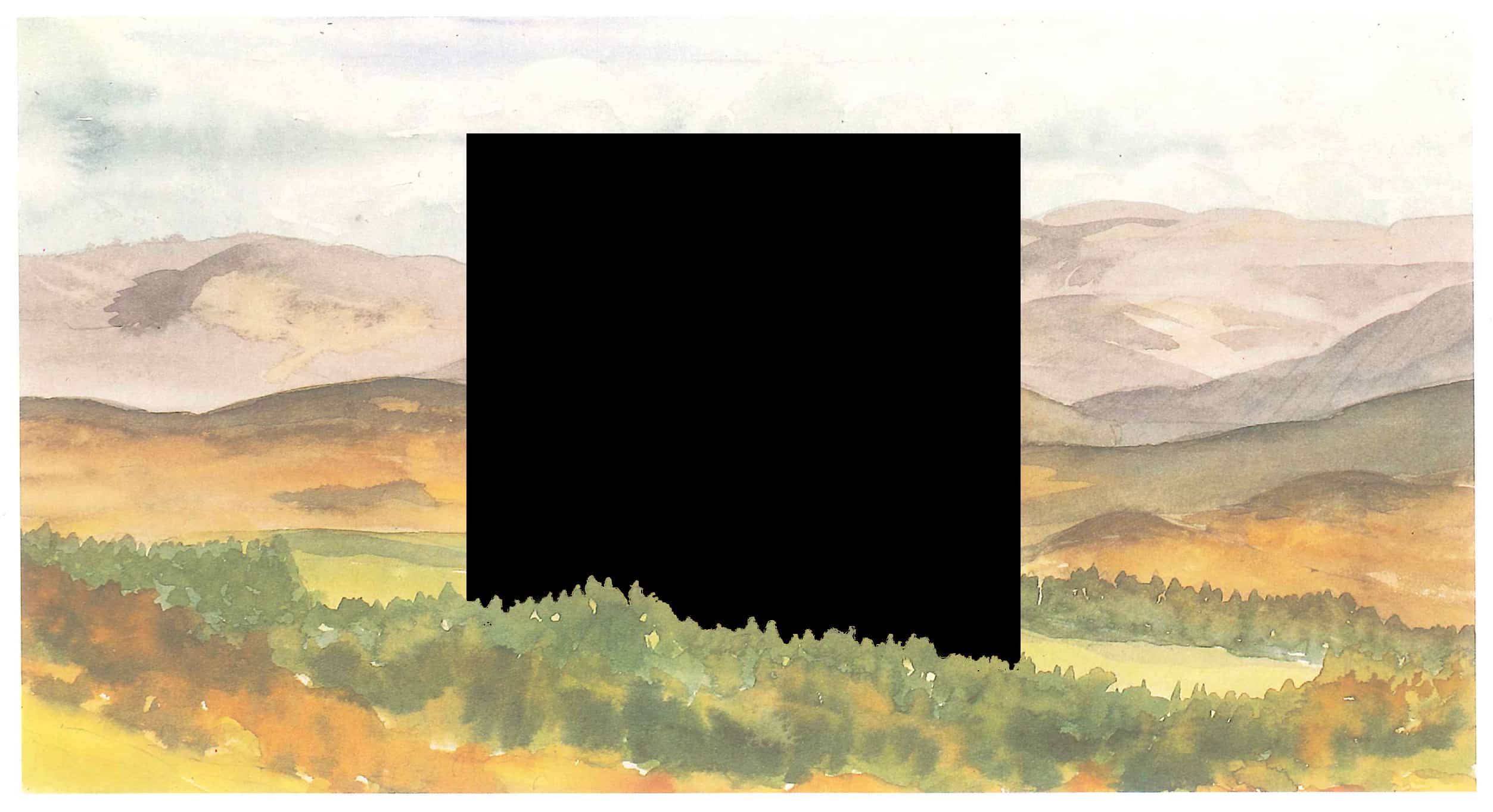

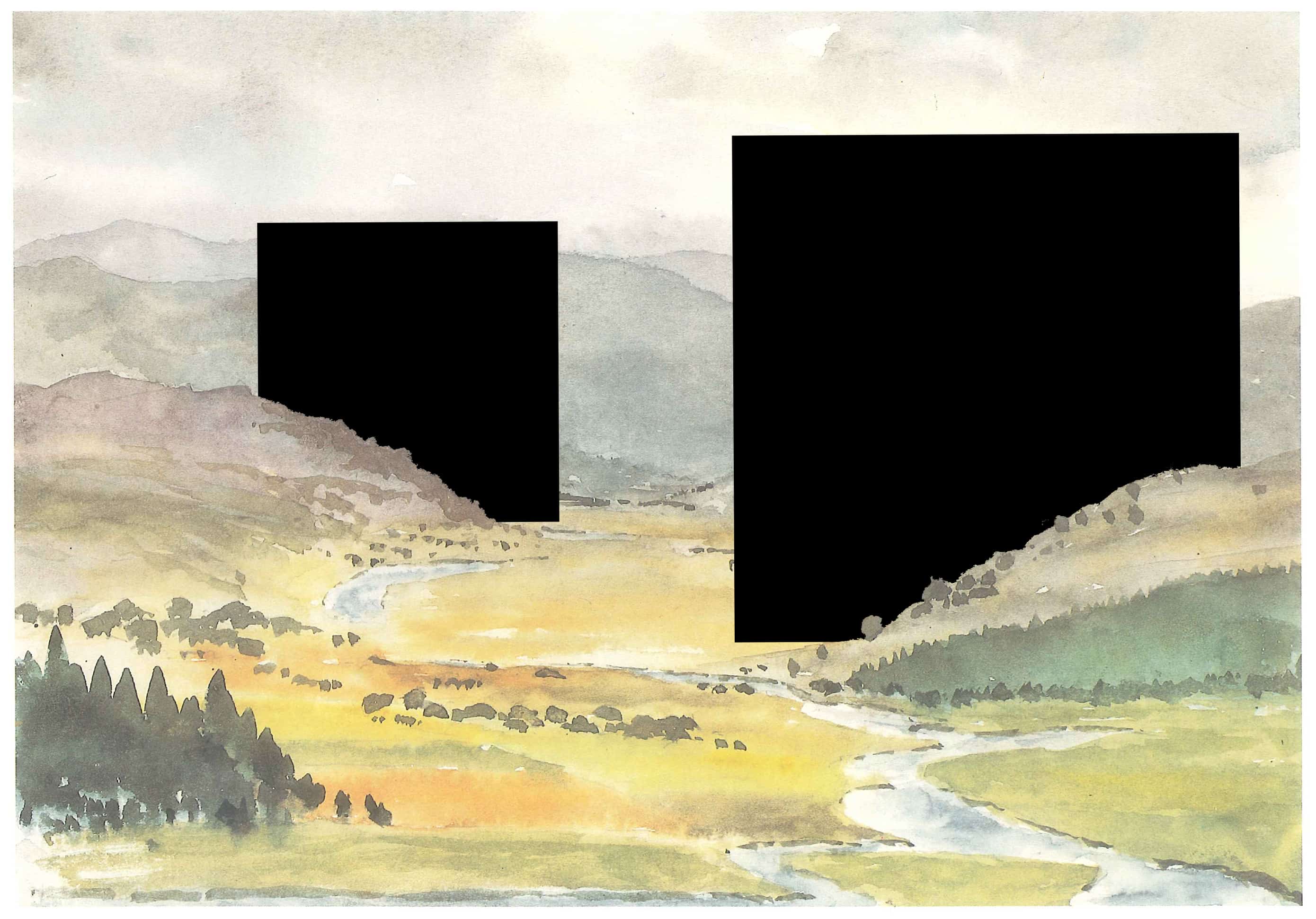

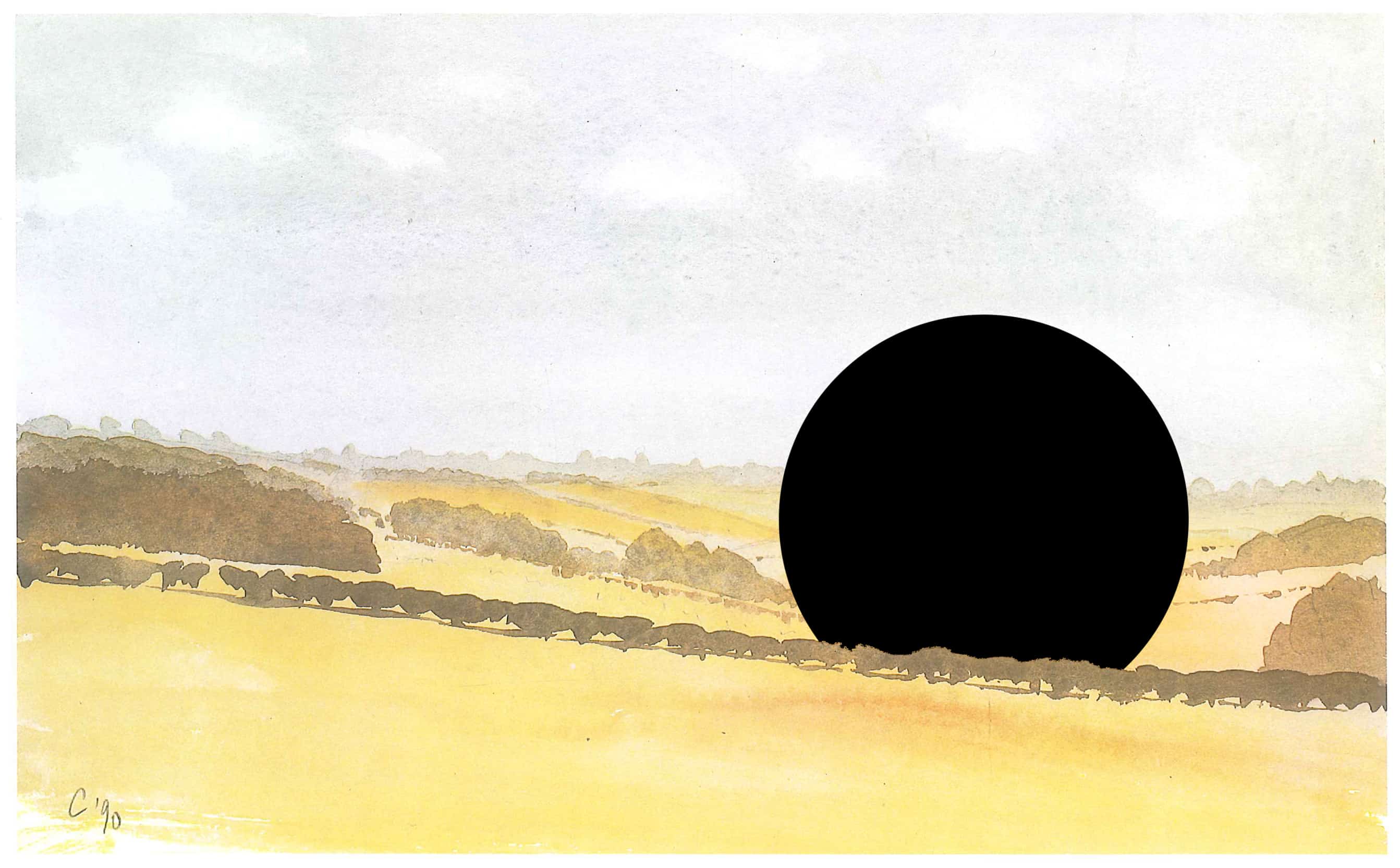

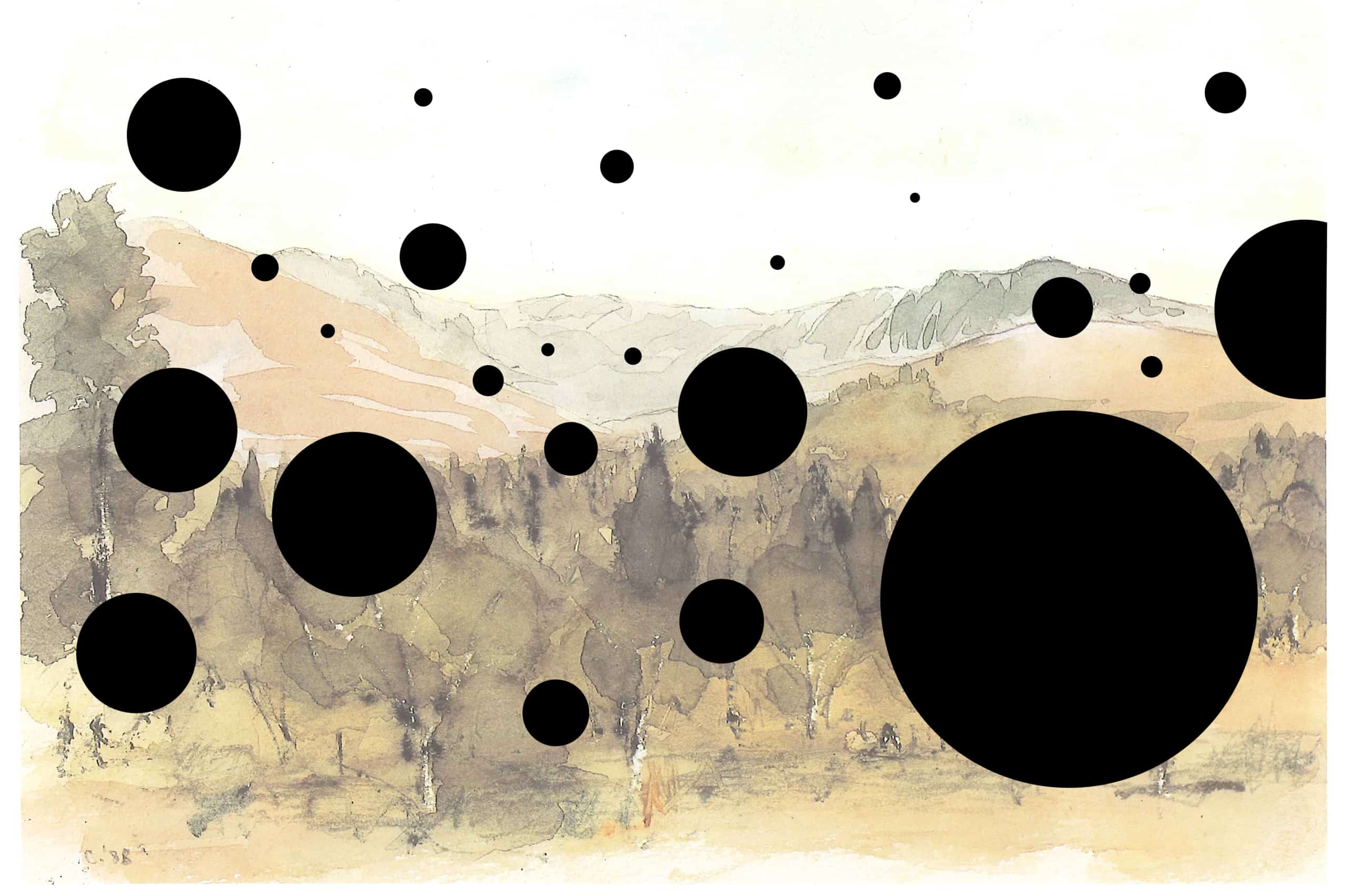

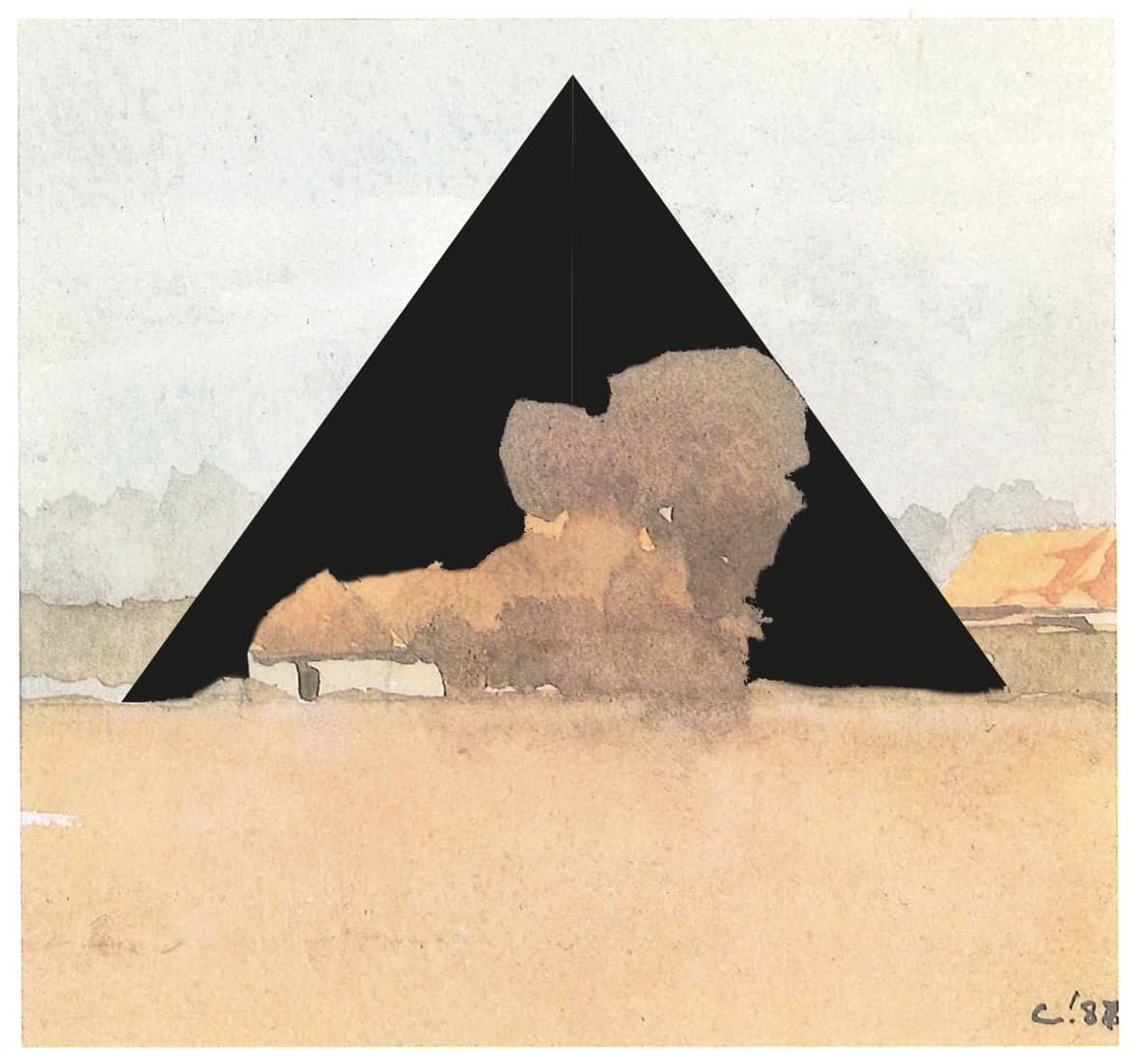

This is a small set of drawings from a wider exploration of the possibilities of digital culture on drawing. Often these are seamless collages made of multiple sources. But these are different. They are watercolours by Prince Charles that have had the most simple and blunt additions (or are those big black shapes erasures?).

It’s almost too perfect to resist: watercolours, landscape, Prince Charles.

Here we see a very particular vision of Britain, one whose subject, media and author are steeped in the the relationship of power to landscape, and to everything that landscape contains. The sentimental depiction, however, goes out of its way to hide these qualities: a hazy wash of nostalgia disguises the landscape. Especially when depicted by the heir to the throne, this biscuit-tin feeling for landscape is far from innocent. We have seen how destructive nostalgia for imagined pasts can be. Ill defined ‘pasts’ exclude the complexities and challenges of modernity and use false ideas of tradition and history to shape the future.

As in politics, so too in architecture. I imagine these interventions into (and/or deletions of) the Prince’s paintings as a form of architectural representation that intervenes in an idea of landscape. Blind spots and black holes puncture the scene creating visual interruptions that remain obscure: UFO‘s, monumental structures, or are they holes in the Princes’ visual field? Abstract rather than representational, they disallow the original vision, countering the sentimentality, the narrative and ideological ‘proposition’ they contain (which includes but is not limited to: a particular idea of nature, a false narrative of continuity and tradition, power ‘naturalised’ into the landscape, and so on).