A Common Treasury

A billboard poster commissioned by Rumi Bose and Aldo Rinaldi for London Festival of Architecture.

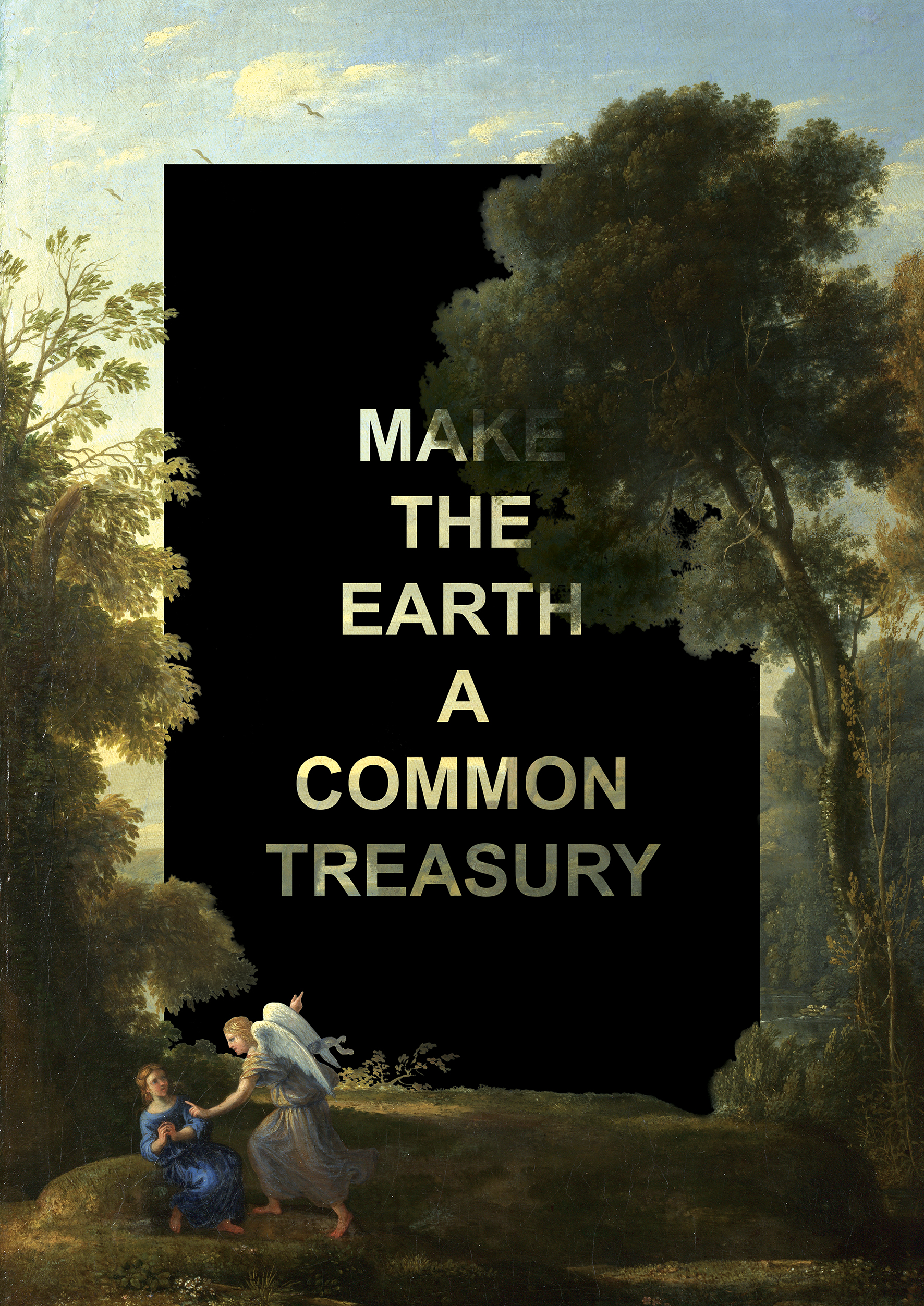

Repeal Enclosure features Claude Lorrain’s Landscape with Hagar and the Angel (1646) obscured by a large black rectangle emblazoned with words from the Digger’s True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649).

Repeal Enclosure argues that the Picturesque landscape is intertwined with the destruction of the commons through acts of enclosure. But it also suggests a new coalition: That picturesque’s romantic sensibility could be multiplied by the Digger’s dream of the common wealth of the land.

Picturesque landscapes look natural but are far from it. They required tremendous wealth and intense labour: Villages were moved, rivers dammed to flood valleys, forests rearranged, all for the sake of a certain kind of view – views that looked like the paintings of Claude, Poussin and others.

These idealised and imaginary scenes had became popular with the English aristocracy and the paintings became blueprints for designers like William Kent and Capability Brown to create landscapes that looked like the paintings their clients liked so much. All of this to give the appearance of nature. Or perhaps as a slight of hand to naturalise power into something so undebatable as idyllic nature itself.

The roots of the picturesque are not only aesthetic, they are legal too. The process of land enclosure began in earnest in the 17th century. Enclosure assembled what had previously been common lands, with common rights of access, grazing and growing. Between 1604 and 1914, over 5,200 individual enclosure acts were passed, radically reorganising the English landscape. The beauty of the picturesque was only possible because of enclosure, its romantic beauty based on dispossession and exclusion.

The Diggers, through publications including Gerald Winstanley’s A Common Treasury and settlements such as on St George’s Hill (now, obviously, a golf course) set out a vision of landscape based on the shared common wealth of the land. Their radial propositions were met with attacks, arson and arrest.

The paintings of Claude and the actions of the Diggers occur at the same moment in time. They offer two different visions of the world, two different images of beauty, two different relationships to nature. Repeal Enclosure imagines a different fork of history, one where their ambitions and dreams combine: A digger picturesque,